❌ Why No Delta is Found on the Western Coast of India

The absence of deltas on the western coast of India is due to a combination of geological, geomorphological, and hydrological factors. Unlike the east coast, which is dotted with major deltas, the west coast lacks the necessary conditions for delta formation.

✅ Key Reasons:

- Geological Structure

- The western coast is bordered by the Western Ghats, made of hard, resistant rocks.

- These rocks inhibit sediment deposition, which is essential for delta formation.

- Short and Limited Rivers

- West-flowing rivers like the Narmada, Tapi, and Mandovi have shorter courses and steep gradients.

- They carry less water and sediment, reducing delta-building potential.

- Low Sediment Load

- These rivers originate close to the coast and have less opportunity to collect sediment.

- Minimal sediment means insufficient material to build deltaic landforms.

- Strong Coastal Currents

- The West India Coastal Current and the Somali Current are active in this region.

- These disperse sediments away from the coast, preventing accumulation.

- Tectonic Uplift

- The region is tectonically active, with faulting and uplift disrupting sediment deposition.

- This also results in a steep and uneven coastal profile, unsuitable for delta formation.

- Wave Action

- The Arabian Sea on the west has high-energy waves and strong tidal forces.

- These waves erode and disperse sediments at river mouths instead of allowing them to settle.

📌 In Contrast:

- The east coast has a wide continental shelf, gentle slope, and large river systems like the Ganga, Godavari, and Krishna that deposit huge amounts of sediments, forming large deltas.

✅ Conclusion:

The western coast of India lacks deltas due to its rocky terrain, short rivers, minimal sediment load, strong coastal currents, and active wave dynamics, all of which prevent the accumulation of materials needed to form deltas.

Delta vs Estuary

| Basis | Delta | Estuary |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A landform formed by deposition of sediments at the mouth of a river. | A funnel-shaped inlet where a river meets the sea, with mixing of freshwater and seawater. |

| Sediment Deposition | High – sediments are deposited, forming new land. | Low – sediments are mostly carried away by tides. |

| Shape/Form | Triangular or fan-shaped landmass | Funnel or V-shaped widening toward the sea |

| Water Flow | Slow, due to obstruction from sediment build-up | Fast, due to tidal action and absence of deposition |

| Coastal Features | Creates distributaries, islands, marshes | No distributaries; may have mudflats or mangroves |

| Examples in India | Sundarbans Delta (Ganga-Brahmaputra), Godavari Delta | Narmada Estuary, Tapi Estuary, Mandovi Estuary |

| Typical Coast | Common on East Coast of India (gentle slope) | Common on West Coast of India (steep slope) |

✅ In Simple Terms:

- A delta builds land out into the sea due to sediment deposition.

- An estuary is where river water and sea water mix, with tidal influence and little sediment buildup.

📌 Conclusion:

🏝️ Comparison of Island Groups: Bay of Bengal vs Arabian Sea

| Feature | Bay of Bengal (Andaman & Nicobar Islands) | Arabian Sea (Lakshadweep Islands) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Formed due to collision of Indian Plate with Burma Minor Plate (tectonic origin). | Formed by coral deposition – part of Reunion Hotspot volcanism. |

| Geological Structure | Made of granitic rocks; part of submarine mountain chains. | Entirely coral atolls and reefs; very low elevation. |

| Major Island Types | Divided into North, Middle, and South Andaman islands. | Includes Amindivi, Laccadive, and Minicoy islands. |

| Location (Latitude/Longitude) | Between 6°N – 14°N and 92°E – 94°E. | Between 8°N – 12°N and 71°E – 74°E. |

| Highest Point | Saddle Peak (737 m) in North Andaman. | Mostly flat islands, rarely rising above 5 meters. |

| Vegetation | Equatorial-type vegetation (dense forests). | Mainly littoral (coastal) forests. |

| Channel Separation | Ten Degree Channel separates Andaman from Nicobar islands. | Nine Degree Channel separates Laccadive from Minicoy. |

| Inhabitants | Indigenous tribes: Jarawas, Onge, Shompen. | Majority Muslim population; settlers mainly from Kerala. |

| Languages | Tribal languages. | Malayalam is widely spoken. |

| Volcanic Activity | Barren Island – India’s only active volcano is here. | No volcanic activity. |

| Number of Islands | Approx. 572 islands. | Approx. 36 islands. |

| Strategic Importance | Important for naval base & marine trade routes in eastern waters. | Important for maritime surveillance & fisheries in the west. |

✅ Conclusion:

The Andaman & Nicobar Islands are volcanic, mountainous, and forested, reflecting a tectonic origin, while the Lakshadweep Islands are low-lying coral atolls, shaped by marine processes. Both are vital for India’s strategic, ecological, and cultural diversity.

🌊 River Basin

Watershed

- A watershed is a smaller sub-unit within a river basin. It refers to the land area that drains into a particular stream, river, lake, or other water body.

- Watersheds are defined by natural ridgelines or elevated areas from which water flows in different directions.

- They are crucial for understanding local hydrology, managing water quality, and planning for land use, agriculture, and conservation.

- Watersheds are commonly used as planning units for water resource management at the local or regional scale.

✅ Key Difference:

| Aspect | River Basin | Watershed |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Larger, may cover thousands of square kilometers | Smaller, localized areas within a basin |

| Scope | Drains entire river system (main river + tributaries) | Drains into a single stream or smaller water body |

| Use | Regional hydrological studies | Local water management, conservation, and planning |

🔁 Hierarchy Example (Ganga System):

- River Basin: Ganga River Basin

- Tributaries: Yamuna, Ghaghara, Son, etc.

- Watersheds: Yamuna watershed, Son watershed, etc.

Each tributary or segment of the river system has its own watershed, and together, these make up the entire basin.

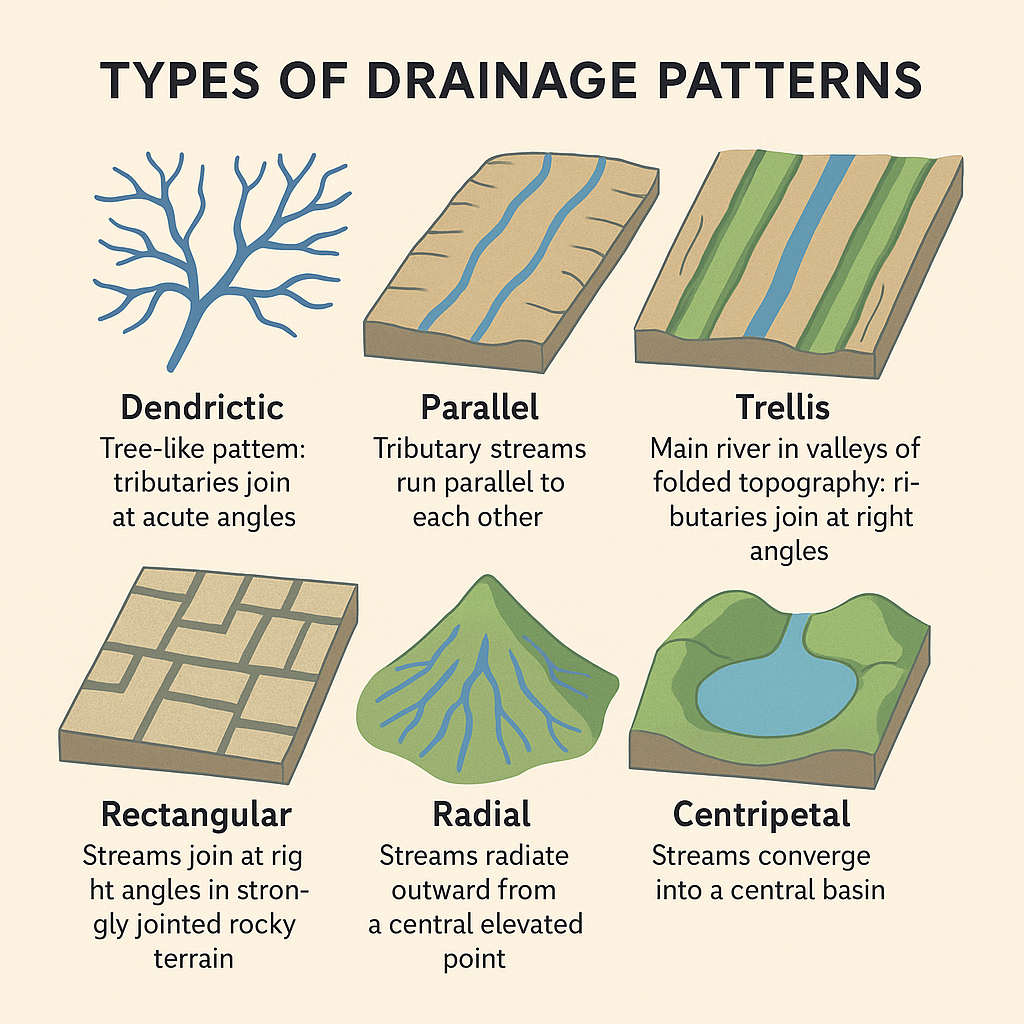

🏞️ DRAINAGE PATTERN

A drainage pattern refers to the spatial arrangement formed by rivers and their tributaries as they flow across the terrain.

📌 Factors Influencing Drainage Pattern:

- Topography (slope of the land)

- Geological structure (rock types, faults, folds)

- Water volume and velocity

- Nature of surface rocks and their resistance to erosion

🔶 Types of Drainage Patterns

1. Dendritic Drainage Pattern

- Most common type; resembles tree branches or roots.

- Forms on uniform rock surfaces without structural controls.

- Tributaries join the main river at acute angles (< 90°).

- Example: Rivers in the Northern Plains – Ganga, Indus, Brahmaputra.

2. Parallel Drainage Pattern

- Develops on steep slopes or elongated landforms.

- Streams run parallel to each other with minimal branching.

- Example: Rivers flowing from the Western Ghats – Godavari, Krishna, Kaveri, Tungabhadra.

3. Trellis Drainage Pattern

- Develops in areas of alternating hard and soft rocks (folded topography).

- Main streams flow in valleys (synclines); tributaries join at right angles (90°).

- Example: Rivers in the outer Himalayas, some parts of Ganga basin.

4. Rectangular Drainage Pattern

- Found in faulted or jointed rocky terrains.

- Streams follow lines of weakness, creating a grid-like or rectangular pattern.

- Tributaries join at sharp angles, often near 90°.

- Example: Rivers of the Vindhyan region – Chambal, Betwa, Ken.

5. Radial Drainage Pattern

- Streams radiate outward from a central elevated point, such as a volcano or dome.

- Example: Rivers from Amarkantak Hills – Narmada, Son.

6. Centripetal Drainage Pattern

- Opposite of radial: Streams converge into a central basin or depression.

- Common in inland drainage basins or playa lakes.

- May form salt flats after evaporation.

- Example: Loktak Lake in Manipur.

✅ Conclusion:

Drainage patterns reveal much about a region’s geological history, rock structure, and topography. Studying them helps in hydrological planning, flood control, and environmental conservation.

🌊 Interlinking of Rivers in India

✅ What is Interlinking of Rivers (ILR)?

The Interlinking of Rivers (ILR) programme aims to connect rivers with surplus water to those with deficient flow, through a network of canals, dams, and reservoirs. The objective is to optimize the use of India’s water resources for irrigation, drinking water, flood control, and hydropower.

🔗 Key Examples of ILR Projects:

- Ken–Betwa Link Project (first under implementation)

- Godavari–Krishna–Pennar–Cauvery Link

- Damanganga–Pinjal Link

- Par–Tapi–Narmada Link

🏛️ Institutional Mechanism:

- National Interlinking of Rivers Authority (NIRA):

A proposed autonomous agency for planning, implementation, and monitoring of ILR projects.

✅ Socio-Economic Advantages of River Interlinking

1. Water Resource Management

- Redistribution of water from surplus to deficit areas.

- Helps mitigate droughts and floods by balancing water availability.

2. Agriculture & Food Security

- Enhanced irrigation potential in rain-fed areas.

- Supports multiple cropping and increases agricultural productivity.

- Boosts food security.

3. Rural Development

- Job creation in construction and maintenance of canals, reservoirs, and related infrastructure.

- Improves rural infrastructure and connectivity.

4. Hydropower Generation

- Potential for renewable energy from canal and reservoir-based hydropower stations.

- Reduces dependence on fossil fuels.

5. Inland Navigation & Trade

- Development of inland waterways for cheaper and eco-friendly transport.

- Promotes regional economic integration.

6. Flood Control

- Diversion of excess monsoon water helps prevent flooding in river basins.

- Reduces disaster-related losses.

7. Urban Water Supply

- Supplies drinking and industrial water to water-scarce urban centers.

- Reduces dependence on overdrawn groundwater.

8. Tourism & Recreation

- Large water bodies and reservoirs may boost ecotourism and water-based activities.

- Generates local revenue and supports service-sector jobs.

⚖️ Conclusion:

The interlinking of rivers offers numerous socio-economic benefits, including water security, agricultural growth, and infrastructure development. However, the project must be pursued with caution due to potential ecological, environmental, and social impacts. Comprehensive impact assessments, public consultations, and sustainable planning are essential before large-scale implementation.

🏞️ Comparison: Himalayan vs Peninsular Drainage Systems

| Aspect | Peninsular Rivers | Himalayan Rivers (Extra-Peninsular) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Geologically older, some as old as the Precambrian period | Younger, except some antecedent rivers like Indus, Ganga |

| Nature | Mostly consequent or rejuvenated rivers | Include antecedent and inconsequent rivers |

| Basin Size | Generally have small basins (except Godavari) | Typically have large basins (e.g., Ganga, Brahmaputra) |

| Channel Characteristics | Shallow, broad channels, close to base level | Deep, narrow channels with gorges, waterfalls, etc. |

| Erosional Activity | Mostly lateral erosion, low vertical erosion | Both vertical and lateral erosion are active |

| Flow Velocity | Slow-moving, especially in flat terrains | Swift in upper courses, sluggish in plains |

| Sediment Transport | Low carrying capacity, depositional in nature | High carrying capacity, active in erosion and deposition |

| Meandering | Create shallow meanders | Create sharp meanders, oxbow lakes in plains |

| Navigability | Mostly non-navigable due to seasonal nature | Largely navigable in plains due to perennial flow |

| Seasonality | Mostly seasonal (rain-fed) | Perennial (fed by glaciers and rain) |

| Source | Originate from Western Ghats or Plateaus | Originate from Himalayas (glaciers and snowfields) |

| Stage of River | In the senile (old) stage | In the late youthful stage |

| River Capture | Rare or absent | Common due to active erosion and topographical changes |

| Hydropower Potential | Utilized for projects like Hirakud, Koyna, Nagarjuna Sagar | Major multi-purpose projects: Bhakra, Tehri, Salal |

| Mouth Type | Form deltas (Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery); some form estuaries (Narmada, Tapi) | Mostly form large deltas (e.g., Sundarbans Delta) |

✅ Conclusion:

✅ Definition:

A river regime refers to the seasonal variation in the flow of water in a river over the course of a year.

It reflects how climatic factors like rainfall and snowmelt affect the volume and timing of river discharge.

🏔️ Himalayan River Regimes

- Himalayan rivers are perennial — they receive water from glacial melt in summer and monsoonal rains in the rainy season.

- Hence, their regimes are both glacio-nival (snow-fed) and monsoonal.

🔹 Ganga River at Farakka:

- Area: 9,51,600 sq. km

- Minimum flow: January–June

- Maximum flow: August–September (monsoon peak)

- Maintains moderate flow before monsoon due to Himalayan snowmelt.

- Discharge: Max ~45,000 cusecs, Min ~1,300 cusecs

- Regime type: Monsoonal with glacial supplement

🔹 Jhelum River at Baramulla:

- Area: 12,494 sq. km

- Peak discharge: May–June (earlier than Ganga) due to early snowmelt

- Discharge: Max ~600 cusecs, Min ~50 cusecs

- Variation is less extreme than the Ganga

- Regime type: Primarily snowmelt-driven

🪨 Peninsular River Regimes

- Peninsular rivers are mostly seasonal and rain-fed.

- Their regimes depend entirely on the monsoon rainfall.

- No glacial source, hence large seasonal fluctuations.

🔹 Narmada River at Garudeshwar:

- Area: 89,345 sq. km

- Very low flow from January to July

- Peak flow: August (monsoon onset)

- Discharge: Max ~2,300 cusecs, Min ~15 cusecs

- Regime type: Sharp monsoonal rise and fall

🔹 Godavari River at Polavaram:

- Area: 2,99,320 sq. km

- Shows a double peak:

- May–June (due to pre-monsoon convectional rain)

- July–August (monsoon peak)

- Discharge: Max ~3,200 cusecs, Min ~50 cusecs

- Regime type: Double monsoonal peak

📊 Key Differences: Himalayan vs Peninsular River Regimes

| Aspect | Himalayan Rivers | Peninsular Rivers |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Perennial (snow + rain-fed) | Seasonal (rain-fed only) |

| Regime Type | Glacio-monsoonal | Monsoonal |

| Flow Variation | Moderate variation throughout the year | Sharp rise & fall with monsoon |

| Double Peak | Rare | Seen in rivers like Godavari |

| Discharge Stability | More stable due to snowmelt | Highly variable |

| River Examples | Ganga, Yamuna, Jhelum, Brahmaputra | Godavari, Narmada, Krishna, Mahanadi |

✅ Conclusion:

The river regime reflects the climatic and geological control over river systems. While Himalayan rivers show stable, perennial flow with glacial input, Peninsular rivers show high seasonal dependence on the monsoon, making them more variable.

🌊 Comparison: East-Flowing vs West-Flowing Rivers of the Peninsular Plateau

| Aspect | East-Flowing Rivers | West-Flowing Rivers |

|---|---|---|

| Direction of Flow | Flow eastward into the Bay of Bengal | Flow westward into the Arabian Sea |

| Gradient | Follow a gentle slope from west to east | Steeper slope from Western Ghats to the west coast |

| Length | Generally longer rivers | Relatively shorter, except Narmada & Tapi |

| Mouth Type | Form deltas | Mostly form estuaries |

| Drainage Pattern | Dendritic or trellis patterns common | Often rectangular or sub-parallel patterns |

| Volume of Water | Carry more water due to larger catchment areas | Carry less water, smaller catchment areas |

| Sediment Deposition | High — suitable for delta formation | Low — estuarine mouths due to wave action |

| Navigation | Some rivers are partly navigable in lower reaches | Mostly non-navigable due to steep gradients |

| Examples | Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery, Mahanadi | Narmada, Tapi, Mahi, Mandovi, Sabarmati |

| Hydropower Potential | Moderate, used mostly for irrigation | High, due to steep gradients and narrow gorges |

| Tributaries | Have numerous tributaries joining at acute angles | Fewer tributaries; often join at right angles |

| Landforms Created | Deltas, floodplains, meanders | Gorges, rapids, waterfalls |

✅ Conclusion:

East-flowing rivers dominate the Peninsular Plateau, playing a crucial role in agriculture and delta formation, while west-flowing rivers, though fewer, are vital for hydropower and flow through steep terrain. Their contrasting behavior reflects the geomorphology and slope of the Indian landmass.

🌊 Types of Drainage Systems in Peninsular India

Peninsular India has a complex drainage system shaped by ancient geological formations, plateau structures, and monsoonal rainfall. The rivers are mostly seasonal, rain-fed, and follow mature courses with broad, shallow valleys.

🔷 1. East-Flowing Drainage System

- These rivers flow eastward and drain into the Bay of Bengal.

- They form extensive deltas due to gentle slope and high sediment deposition.

- The rivers have larger basins and are more numerous.

🗂️ Examples:

- Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery, Mahanadi, Vaigai

🔷 2. West-Flowing Drainage System

- These rivers flow westward and drain into the Arabian Sea.

- They form estuaries, not deltas, due to high gradient and strong tidal activity.

- Shorter in length and steeper in gradient, leading to rapids and waterfalls.

🗂️ Examples:

- Narmada, Tapi, Mahi, Sabarmati, Periyar, Mandovi

🔷 3. Inland Drainage System

- Some rivers in arid and semi-arid regions do not reach the sea.

- They drain into inland basins or salt lakes, forming endorheic basins.

🗂️ Examples:

- Luni River (Rajasthan) — drains into the Rann of Kutch

- Rivers in the interior Deccan Plateau that vanish in deserts

🔷 4. Sub-Parallel Drainage System

- Rivers flow almost parallel to each other, typical of elongated plateau slopes.

- Common in regions with uniform lithology and slope, like parts of Tamil Nadu and Chhattisgarh.

✅ Conclusion:

The drainage systems in Peninsular India reflect the ancient, stable geological structure, with rivers shaped by monsoonal rainfall, plateau slope, and rock formations. Both east- and west-flowing rivers play vital roles in agriculture, hydropower, and water supply.